20,000 Birthday Steps

Earthshine reader —

It's me (Dazé), and I'm … terrified.

This is issue #001 or, put differently, the second newsletter I write in my entire life. What I'm trying to say is … I don't know what the hell I'm doing.

Anyway, to commemorate the special occasion, I've chosen a special walk.

It was March 11, 2022 — my birthday. I had recently moved to Japan with my wife and a two-year visa. Upon arrival, we were asked to undergo a one-week quarantine in a little Tokyo apartment. You can imagine how many outings we did once that week was over; this one was no exception.

As it happened, my birthday fell on a Friday. Since my wife was working, I decided to take the day off and treat myself to a long walk from Minato to Shinjuku. If you ask Google Maps, it will tell you that a walk like that takes about an hour and a half — I did it in four.

The plan was to end in Shinjuku and meet the Mrs at 6 p.m. for a special birthday dinner, followed by a cinema date. Lucky for me, I didn't need to wait that long to be spoiled with gifts: The weather gods had blessed me with blue skies and no wind — perfect shooting conditions.

It turns out I didn't photograph that much during the first hour. This wasn't surprising; I didn't exactly need a camera to keep myself entertained while exploring the most populated prefecture in Japan.

This first image was taken shortly after I entered the Aoyama Cemetery in Minato. Funny enough, I didn't intend it; a car happened to pass by, and as I gave way, my thumb accidentally pressed the shutter — I only discovered it once I got home.

It's an interesting frame, though. The car door reflection of the cross and tombstones proves to be rather symbolic of the place I was in, and yet polar opposite to the life-celebrating tone of this particular walk.

Onto the first image I can take full credit for. One of the culture shocks I felt when I first came to Japan in 2017 was the compact design element. Take cars, for example; ignoring the luxury brands, most consumer vehicles look more square than the ones in the West. You may not appreciate it in this picture, but the minivan is both small and boxy — dare I say cute?

What I like about this picture is the centre framing of the subject — at the top by the awning of branches, at the bottom by the crawling shadows, and to the sides by the brigade of tombstones.

As I waited for the pedestrian light, I noticed the yellow colour of the lady's purse and that of the next lady's skirt. Seconds later, the green man lit up and I reacted in an instant, hence the skewed angle.

Upon closer inspection, you could argue that the colour theme extends past the third lady and onto the fourth. I find that these three points of interest create a leading line which, aided by the zebras, helps carry your eyes through the photo.

I was levitating leaning over an overpass. I can't remember if this was next to a TV station or if the production truck was out on a call. Either way, I found the perspective interesting. (Something you'll notice in future photowalks is that I like high vantage points.)

The second thing that sparked my interest was how the scattered cluster of media equipment parallels the shape of the truck. As for the subject, a bit of patience — and luck — was required to include her.

There was a running track just off to the left, so I can only assume this gentleman was taking a breather from an intensive cardio session.

I like how the golden foliage forms two slanting lines leading into the subject. Meanwhile, the other side is a … summer green? It's as if two seasons are about to face off in an epic Waterloo-style clash, and the only thing standing in between them is a tired soul begging for peace from a rather symbolic white base.

It was the walls, their play on depth, and the way the scene converges into a pocket of light that caught my attention as I stumbled upon this tiled building entrance. Moments later, as I was composing the shot, a hardworking man took a turn into the frame and I caught him before he disappeared into the background.

I'm noticing a tendency to capture lone subjects and isolate them further with light and composition in this walk. (This appears to be an intrinsic part of my photography as you'll see in upcoming photowalks — I'm not sure why though.)

I was under an overpass and spotted this deliveryman parked to the side. He might have been talking on the phone — I'm not sure.

I noticed how the daylight reflecting off of the concrete caressed his face, and figured that, by shifting my position a bit, I could align his head so that it appeared framed inside the window. The cherry on top was of course that the minivan was also being bordered; in its case by the metallic column supporting the bridge.

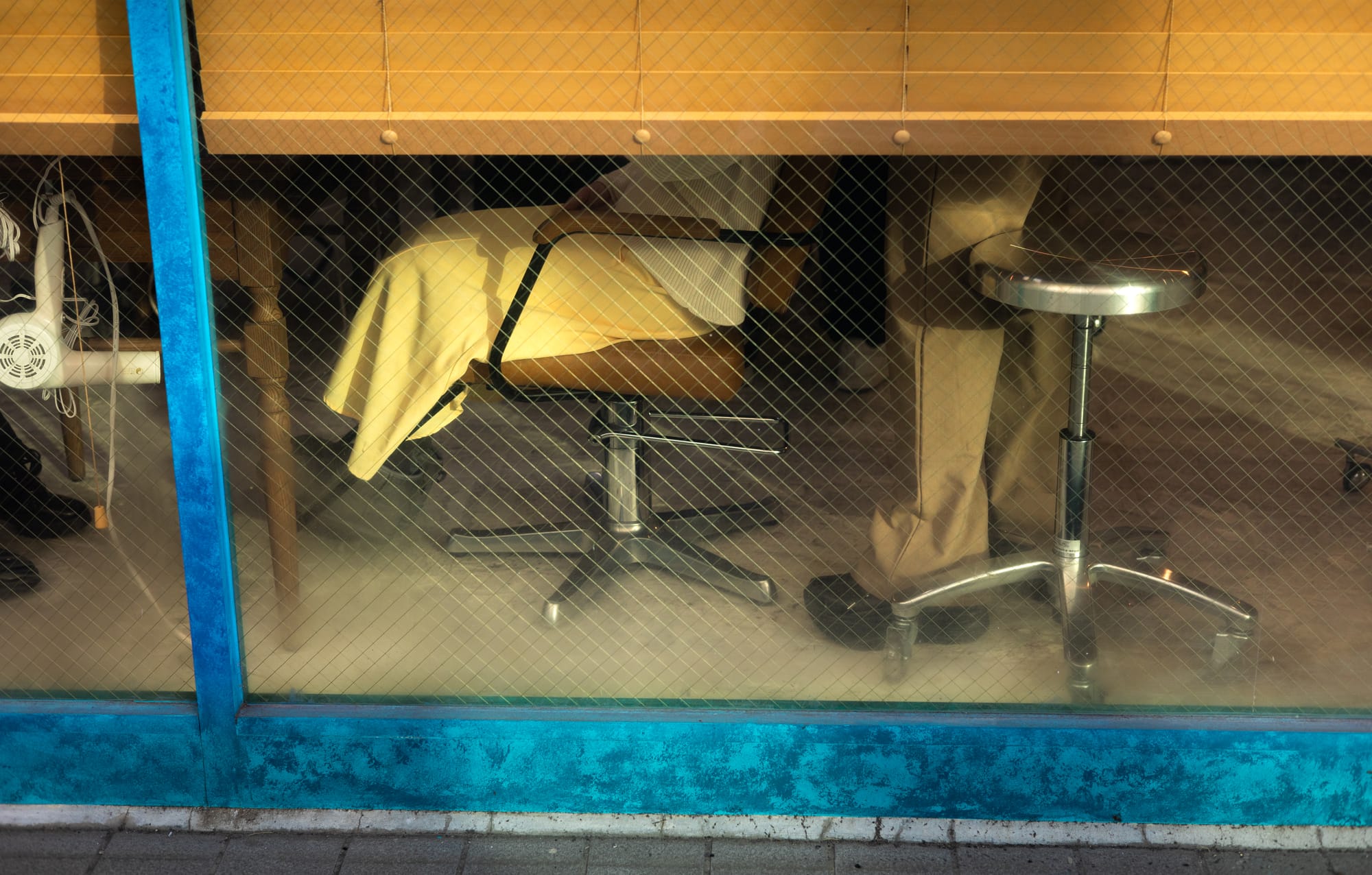

This is one of my favourites from the day. I was in a small street approaching Shinjuku Station when, to my left, I noticed a local hair saloon. The blinds were halfway down, so you couldn't make out the people's faces, creating mystery.

In retrospect, what truly stands out to me is how the pastel-yellow skirt of the lady matches the hue of the blinds while the contrasting blue frame sort of "contains" the whole inside scene. I also adore the blow dryer on the left.

Salarymen are high on the list of photogenic aspects of Japan. This one in particular was headed wherever this bridge structure leads — I can't remember.

What I do recollect is that I waited for him to pass by the light splattered onto the windows of the supporting building. The staggering number of crisscrossing lines is another thing that subconsciously must have made me stop.

This is the Docomo Tower, located near Shinjuku Station. On this day, there was a construction site in the vicinity, and the crane was centre-stage. Tokyo Haneda Airport is also not that far, so planes cruising overhead is a common occurrence.

Looking up, I got the idea of encapsulating all four lofty elements in the same frame — crane, moon, tower, and plane. What surprised me when I got back home was that I had captured more than one plane — can you spot it?

As I entered the street that channels into the heart of Shinjuku, I noticed two ladies dressed in matching fire-orange kimonos hurrying down the sidewalk, no doubt running late. Anticipating a good moment, I decided to catch up with them. Suddenly, one of them leaps onto the street and waves into the traffic. A taxi pulls up, and the pair jump in.

The sequence happened so fast that I barely managed to raise my camera and capture this fleeting moment. I wonder if they arrived on time …

Claw machine parlours like these are a common site in Tokyo. They can get remarkably busy at night. At this hour, however, the only activity — apart from all the flashing lights — was this solitary individual debating whether to give the Minecraft machine a go or two.

Come to think of it, I never tried my luck with these machines. I think it's prizes — they take up too much space.

Here's another typical storefront you see in Tokyo: geek shops — I'm a geek myself, but mainly when it comes to Pokémon. Although there were a few pocket monsters on display in this store, it wasn't them that caught my eye; it was the juxtaposition of the grown man surrounded by the flashy toys.

The truth is that "cute culture" is a major component of modern Japan; even the government involves charming mascots to attend diplomatic events. This cultural phenomenon allures me, which makes me wonder if the real reason I captured this image was because I saw myself in that young man …

The light was fading, and so was my energy. I was nearing four hours of walking, which translates to roughly 20,000 birthday steps or about 15 anniversary kilometres. Feeling satisfied, I decided to look for a place to sit down.

During my search, I came across the side of this building and noticed how the bars covering it created an interesting light-and-shadow effect. I was about to hit the shutter when I spotted a lady ascending the escalator — the rest is history.

Fatigue was starting to seep into every fibre of my being. What didn't help was that I hadn't come across a single bench in the last 10 minutes.

As I staggered further into Shinjuku, I turned a corner and noticed this ramen place across the street. It was as if my belly had eyes because I swear I heard it growl at that precise moment.

Remembering what was to come, I dismissed my hunger and raised my camera for one last shot. The waiter — as waiters do — kept dashing from left to right, so freezing him in this place took a few tries.

Despite the countless engrossing things to capture in the bustling streets of Shinjuku, I decided to put my camera away and call it a walk.

For the next hour or so, as I clocked in a few more steps, my stomach grew louder by the minute. During this time, I remember painstakingly avoiding jumping into a convenience store and grabbing a snack.

Eventually, the struggle came to an end in the shape of my wife, who so kindly treated me to an all-you-can-eat called Nabezo. This was my first time trying "shabu-shabu" and "sukiyaki" in a restaurant — and what a treat it was.

After a heavy intake, the two of us staggered to the Shinjuku Piccadilly Cinema to see Robert Pattison portray a somewhat emo iteration of Bruce Wayne. To give you a sense of how full I was, I had to decline popcorn.

D